Semoria F. Mosley

“What goes on in my house… stays in my house?”

I know two things to be true.

“What goes on in my house, stays in my house,” is a phrase I grew up on.

To be born is to carry ancestral karmic debt.

In examining pressures of the U.S. racial wealth gap as it pertains to overworking for stability and intergenerational family estrangement, born are a set of reactionary instances that continue to manifest generationally and domestically. Instances such as the banishment of Black children from their homes, ancestral trauma, guilt, lack of boundaries and secrecy make me interrogate my existence by asking, “What role does incarnation, power and choice play in our upbringing?” Since we all have to be children, that innocence is not only meant to be broken but is also imperative and introductory. Who and what has the right to take our innocence? Selfishly I have asked, why?

bell hooks once said, “Someone can be in a domination of power but still be helpful.”

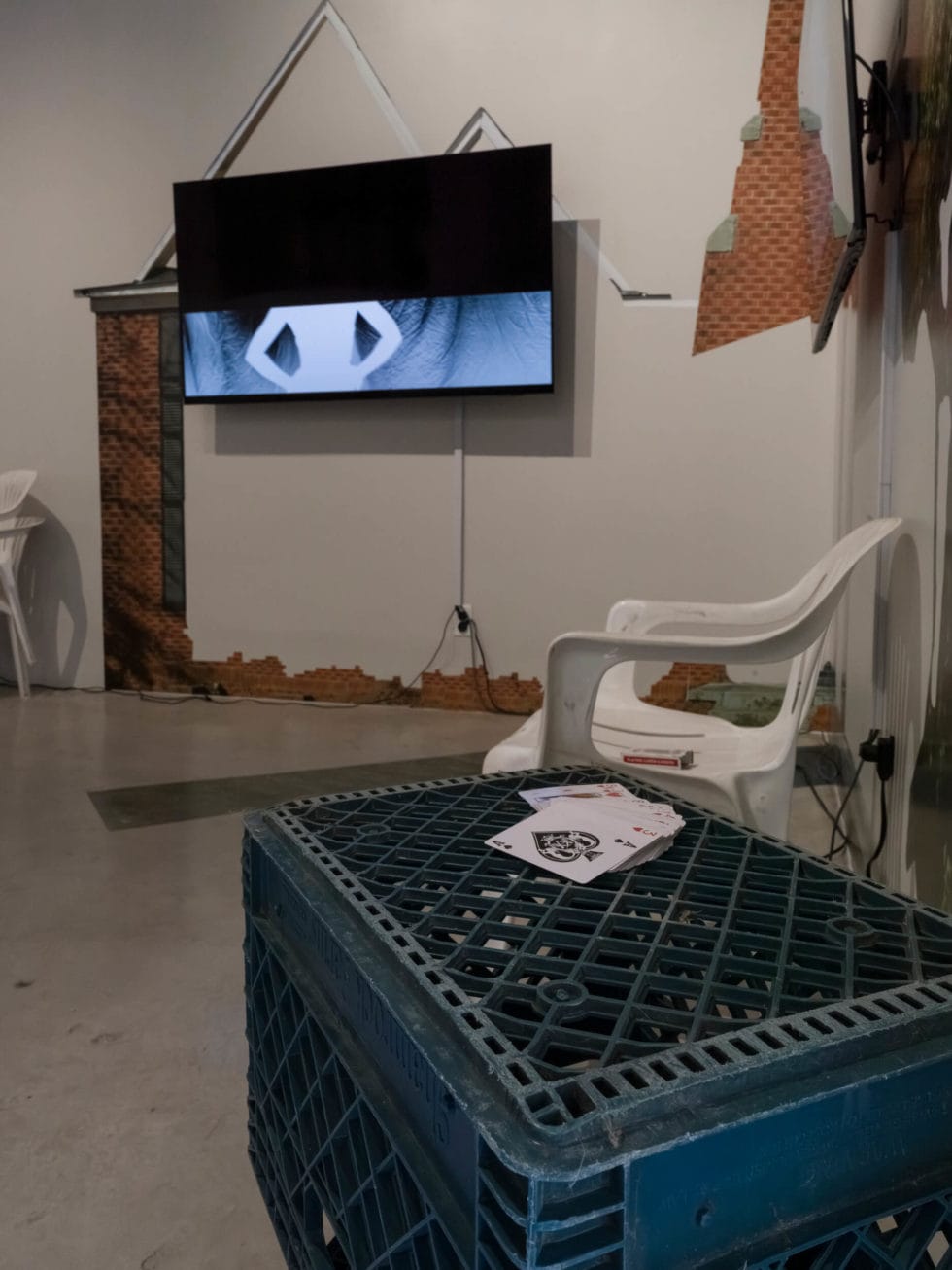

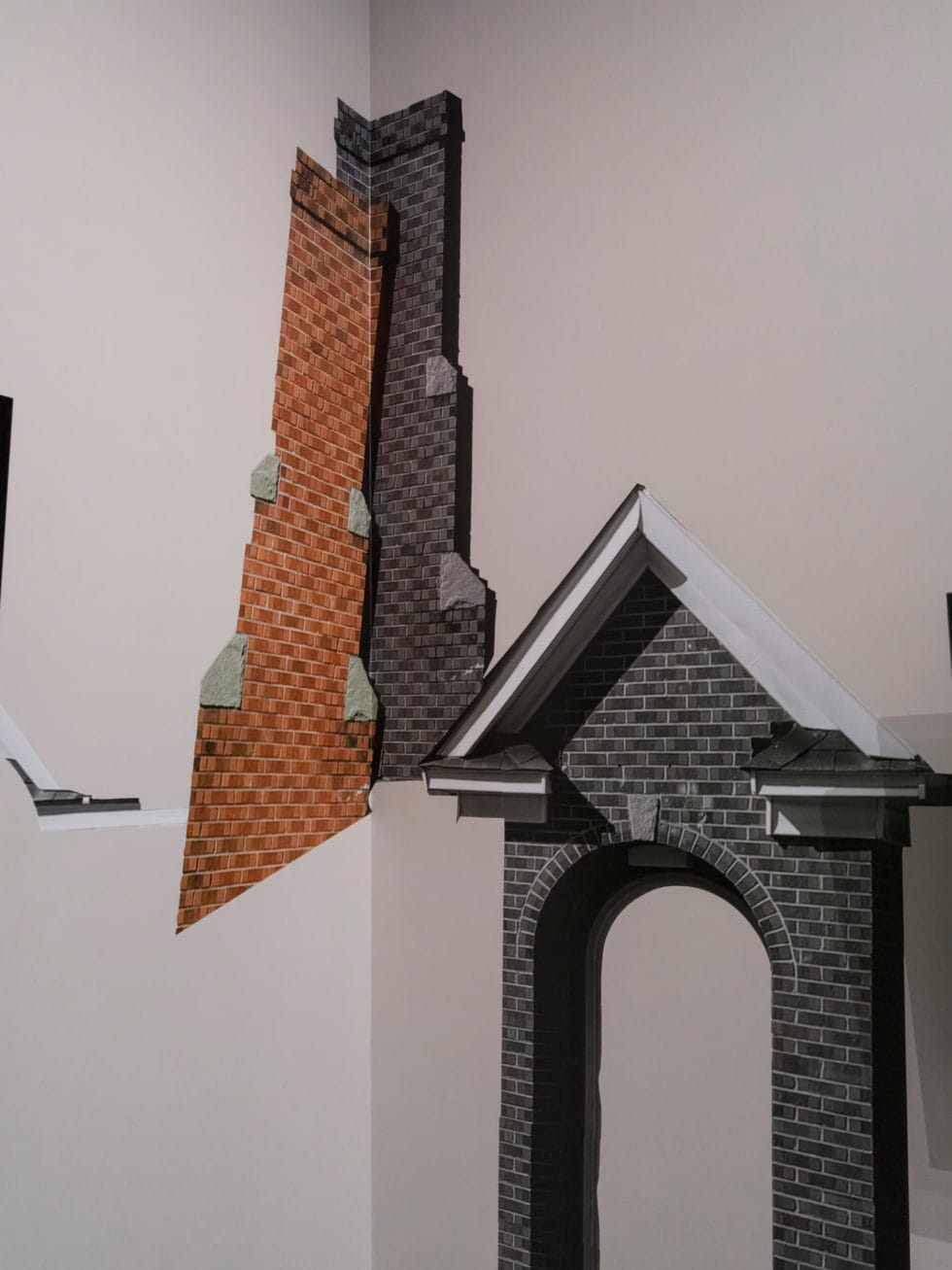

Materialized as a diaristic video installation reflecting on my upbringing in the Deep South as a young girl and an only child, there is an evident connection between contemporary child rearing practices of Black Americans and the tactics of control used on Southern plantation systems.

The phrase was and is used to deter outsiders from tugging on personal and domestic issues – which has historical context. I assert that Black Americans have adopted conservatisms as a survival strategy. The more an enslaved person could keep hidden from their master, the more potential for personal autonomy. Translated to the present, there is shame in being perceived. The domestic space assigned to us is our first incubator for hiding.

Throughout my childhood being directed to the corner meant assuming a position of punishment and embarrassment. Suggesting the corner of the gallery as a point of origin, the work radiates left and right alluding to both opening up and confinement. Largely deconstructed, an image of my childhood home is printed on adhesive vinyl and made to function as a stage for the performance of obedience and disobedience. By purposefully exposing the interiority of domestic space, I situate myself within the realities of dealing with our own mess through transparency, resistance and liberation.

I dedicate this installation to myself and the mothers of my lineage who were neglected. For mothers and fathers who needed to be seen so much that their children were weighted by the choice to disguise emotional unavailability as tough love. To the children who have blossomed into adults that were tasked with proving themselves beyond the capability of proof, perfect ain’t real. To the children that have blossomed into adults but watched their mothers disguise their pain, I don’t know what to say I am still processing.